In the face of demographic challenges, increased international trade and the effects of climate change, animal health is more fundamental than ever to the development and well-being of human populations around the world.

Production animals constitute 40% of the value of global agriculture. They support the income and livelihoods of 1 in 5 people1, mostly in developing countries.

Yet, animal diseases can significantly decrease this potential.

Evaluating the burden linked to these diseases is key to improving our relationship with production animals, and to building a more sustainable world.

This is the goal of the Global Burden of Animal Diseases (GBADs) programme.

The GBADs programme will achieve a better understanding of livestock and aquaculture production systems and their footprint on society and the environment.

Animals can be impacted by a range of health and welfare issues.

Often, farmers have to manage them alone, especially smallholders who have limited access to animal health services and products due to social, financial and geographical constraints.

The global burden of animal diseases is believed to be huge. Yet, it is very difficult to measure. Today, we only have a limited and partial picture of the critical economic challenges related to animal health and welfare.

We are striving to change this.

By gathering available data and developing an innovative methodology, the GBADs programme will determine the economic burden of animal diseases. The findings will inform governmental and non-governmental responses to animal health issues.

We are more aware of highly contagious animal diseases as their consequences can have ripple effects on trade, food supply, and even human health. In addition, many other factors affect animal health and productivity. They include management factors such as nutrition, the risk of accidents or predation, and environmental change. Money is then spent on attempts to prevent or react to potential losses.

Modified from Rushton J., Thonton P.K. & Otte M.J. (1999). Methods of economic impact assessment. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 18 (2), 315 - 342. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.20506/rst.18.2.1172 accessed on 31 March 2022). Rushton J. (2008). – The Economics of Animal Health & Production. CAB International, United Kingdom. 3

We are more aware of highly contagious animal diseases as their consequences can have ripple effects on trade, food supply, and even human health. In addition, many other factors affect animal health and productivity. They include management factors such as nutrition, the risk of accidents or predation, and environmental change. Money is then spent on attempts to prevent or react to potential losses.

Modified from Rushton J., Thonton P.K. & Otte M.J. (1999). : Methods of economic impact assessment. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 18 (2), 315 - 342. http://dx.doi.org/10.20506/rst.18.2.1172. (accessed on 31 March 2022). 3

Rushton J. (2008). – The Economics of Animal Health & Production. CAB International, United Kingdom. 4

Livestock and aquatic animals provide humans with income, nutritious food, clothing, fertilizer, building materials and traction power. Making the best possible use of production animals in agriculture and aquaculture in a humane and environmentally friendly way is of growing importance, as losses impact producers and consumers directly and the whole of society indirectly.

GBADs will contribute to more efficient animal production systems improving therefore livelihoods, general wellbeing and environmental sustainability.

The populations of livestock and aquatic species have never been so high, and these animals use land and water and impact on air quality.

Mt = Million tonnes

(In livestock unit equivalents based on FAOSTAT data)

Adapted from Rushton J. & Bruce, M. (2016). : Using a One Health approach to assess the impact of parasitic disease in livestock: how does it add value? Parasitology, 144 (1), 15 25.

doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000196.5

Globally, 1.3 billion6 people directly depend on food animals for their living. Of these, 600 million are smallholder farmers in some of the world’s poorest countries7. Poor animal health in these countries affects production, exposing farmers to reduced income and well-being.

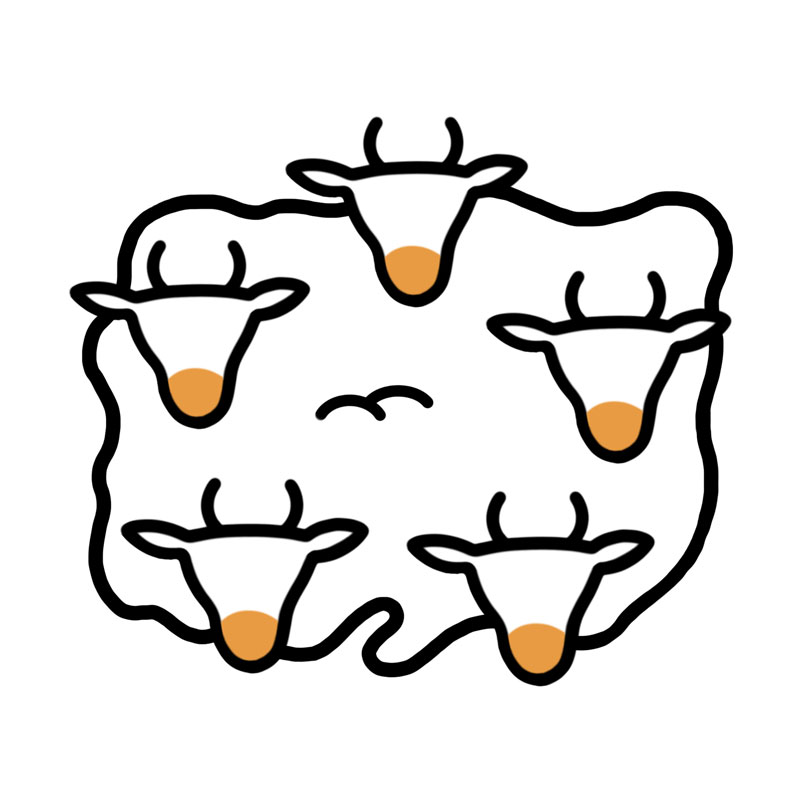

Juanita raises a flock of 12 sheep. She trades them and their wool at local markets.

In the region, a highly contagious disease called foot and mouth disease (FMD) affects livestock production and trade. This could be a threat to Juanita’s earnings. The government has developed a strategy to control FMD, but Juanita has other day-to-day concerns with regard to keeping her family and flock fed and healthy. She needs additional advice and support on sheep nutrition, genetics and parasite control with better access to veterinary products and services.

More targeted support from her government would help her increase the productivity of her flock, and consequently, the wealth and well-being of her family.

GBADs will help governments identify the animal health challenges that have the greatest impact on producers’ livelihoods.

Animal production is intrinsic to providing sufficient access to high-quality protein and is particularly important in countries where malnutrition is frequent. In addition to direct productivity losses, animal diseases can affect how and if livestock products are processed.

Pork is the most consumed meat worldwide, representing 35%9 of global meat consumption. In recent years, African swine fever - a deadly pig disease - has become a major crisis for the pork industry, causing massive losses in pig populations and generating drastic economic consequences. With no effective vaccine, the disease is not only impeding animal health and welfare but has detrimental impacts on the livelihoods of farmers and on food security.

GBADs information will help decision-makers target resources at animal diseases that threaten the food security of at-risk human populations.

The lower productivity of sick animals increases the need for resources to attain a given yield. It leads to needing more animals to achieve the same output, using ultimately more land and water.

Research on terrestrial farming has estimated that two-thirds of agricultural land is dedicated to livestock10; agriculture takes between 70% and 90% of the world’s freshwater11, and a third of this is used on livestock12; livestock are a source of methane (CH4) and indirectly carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and local pollution.

GBADs findings will support a better management of natural resources and will indirectly contribute to limiting the food system’s effect on climate change and environmental degradation.

In rural agriculture-based economies, women comprise two-thirds of low-income livestock keepers13 as animal husbandry is often easier to acquire than other physical and financial assets14. Animals represent a source of income that helps meet specific expenses for the household, such as children’s school fees or medical costs, and is also key to their empowerment. Yet, the work of these some 400 million women is poorly explained in economic terms, and their role remains unrecognised.

Peste des petits ruminants (PPR) is a disease of sheep and goats. Over the last 15 years, it has spread to over 70 countries. It now threatens 80% of the world’s sheep and goats, many of which are owned by female farmers.

The disease is highly contagious and induces heavy drops in production and high mortality in animals. Such significant losses directly impact household incomes, drastically reducing the opportunities to access health care and education, and sometimes leading to diminished social status. Improved understanding of the impact of PPR on the condition of women could help empower them in many countries.

Eradicating PPR requires a major effort over the next 10 years. Understanding the socio-economic impacts of the disease is key to boost the required investments.

GBADs will look at livestock ownership by gender across the world. It is also committed to providing information on the level of gender-sensitive data available.

There has been an increasing emergence of diseases and recurrences of major transboundary animal diseases in recent decades. Three out of five emerging human infectious diseases are of animal origin. Animal diseases also affect food security and human nutrition as they reduce the availability and affordability of high-quality animal products.

Livestock are part of an economic system. The new approach proposed by the GBADs programme will capture this context when evaluating the burden of animal diseases. It will switch from an animal health centered approach to an economic one.

Download timeline

Download timeline

Adapted from GT Patterson et al 2020.

GBADs will support the investment in surveillance and prevention actions to manage and limit the risks of disease emergence from livestock and aquaculture species.

Economics in animal health has traditionally been used to advocate for control strategies against specific diseases, at a given time. GBADs seeks to transform this approach to consider investment needs in the animal health sector in a global socio-economic context. This will enable optimal resource allocation, thanks to evidence-based decision making.

Livestock and aquatic animals are part of an economic system. The new approach proposed by the GBADs programme will capture the wider social and environmental impacts when evaluating the burden of animal diseases. It will also assist in the optimisation of critical resources.

Reaction to specific animal health challenges

A disease becomes important

A strategy is developed

An economic justification is made

A disease control programme begins

Prior to allocation of resources

The socio-economic context is assessed

Resource allocation is analysed

Gaps are identified

Resources are reallocated to target needs

APPROACH

Reaction to specific animal health challenges

APPROACH

Prior to allocation of resources

Adapted from Rushton, J. (2017). : Improving the use of economics in animal health : Challenges in research, policy and education. Prev. Vet. Med., 137 (Pt B), 130 : 139. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.11.020.15

The GBADs programme will help quantify the positive and negative impacts of animal production systems on society and the environment, and will offer solutions to support smallholders, businesses and society as a whole.

A detailed methodology will be developed by a diverse team of researchers, to collect data and produce standardised and comparable information on the economic impact of animal diseases. GBADs will also work with existing information systems such as those in operation at the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (e.g. WOAH-WAHIS, the WOAH PVS Pathway) and at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (e.g. FAOSTAT and Empress-i).

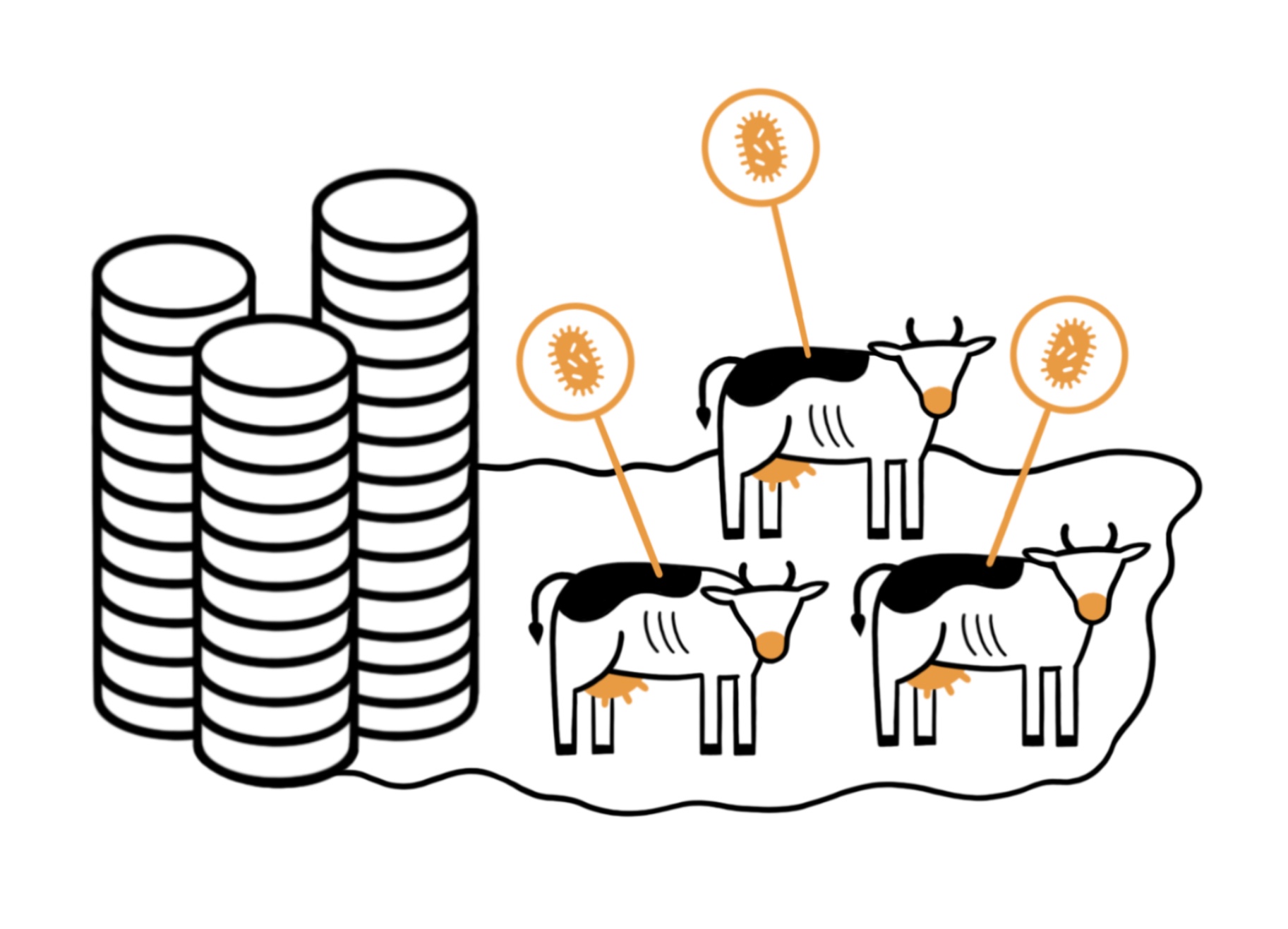

The GBADs programme will provide information at farm and national levels.

Livestock population

Biomass

of animals

Economic investment in animals and infrastructure

Shortfall linked to poor animal health

Loss of production

Money

spent

Economic impact

Who is affected across society

Adapted from Rushton J., Huntington B., […] & Mesenhowski S. (2021). - Roll-out of the Global Burden of Animal Diseases programme. Lancet, 397 (10279), 1045-1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00189-6 16

Why do we need standardised data?

It will allow comparisons of burden over time at a global scale and between:

In the long run, GBADs aims to gather sufficiently detailed data to disaggregate the burden further, for example by socio-economic status, and at intra-household level by gender.

The GBADs programme will apply its methodology to:

The GBADs programme will enable decision-makers in animal health to:

Make investment plans which ensure there are adequate animal health systems.

Allocate resources to problems that most affect the health and well-being of animals and people.

Evaluate animal health investments to ensure they are delivering on societal and environmental outcomes.

GBADs is developing a knowledge engine that will inform decision makers in the public and private sectors, drive policy change and strengthen strategies in order to improve animal health system performance and deliver progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

GBADs will contribute to strengthening the food system for the benefit of society and the environment. It is an example of One Health in action.

WOAH Scientific and Technical Review article

Consult the GBADs website

Read the WOAH PANORAMA on GBADs

Subscribe to the GBADs Newsletter

Follow us

The GBADs programme benefits from the technical and financial support from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, European Commission, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and The Brooke.

1. Thornton P.K., Jones P.G., Owiyo T.M., Kruska R.L., Herrero M., Kristjanson P., Notenbaert A., Bekele N. & Omolo A. (2006). – Mapping climate vulnerability and poverty in Africa: report to the Department for International Development. International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya, 200 pp.

2. Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy.

3. Rushton J., Thonton P.K. & Otte M.J. (1999). Methods of economic impact assessment. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 18 (2), 315–342. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.20506/rst.18.2.1172 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

4. Rushton J. (2008). – The Economics of Animal Health & Production. CAB International, United Kingdom. doi:10.1079/9781845931940.0000.

5. Rushton J. & Bruce M. (2016). Using a One Health approach to assess the impact of parasitic disease in livestock: how does it add value?. Parasitology, 144 (1), 1525. doi:10.1017/S0031182016000196.

6. Ashley S., Holden S. & Bazeley P. (1999). - Livestock in poverty-focused development. Livestock in Development, Crewkerne, United Kingdom.

7. See footnote 1.

8. https://www.wfp.org/zero-hunger.

9. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2014) – Food Outlook biannual report on global food markets. FAO, Rome, Italy. Available at http://www.fao.org/3/i4136e/i4136e.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021)

10. Wirsenius S., Azar C. & Berndes G. (2010). – How much land is needed for global food production under scenarios of dietary changes and livestock productivity increases in 2030? Agric. Syst., 103 (9), 621–638. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2010.07.005.

11. Molden D., International Water Management Institute & Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture (Program), eds. (2007). – Water for food, water for life: a comprehensive assessment of water management in agriculture. Earthscan, London, United Kingdom & Sterling, Virginia, United States of America, 664 pp.

12. Gerbens-Leenes P.W., Mekonnen M.M. & Hoekstra A.Y. (2013). – The water footprint of poultry, pork and beef: A comparative study in different countries and production systems. Water Resour. Ind., 1–2, 25–36. doi:10.1016/j.wri.2013.03.001.

13. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2013). - Understanding and integrating gender issues into livestock projects and programmes. FAO, Rome, Italy, 56 pp. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/i3216e/i3216e.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021) .

14. Herrero M., Grace D., Njuki J., Johnson N., Enahoro D., Silvestri S. & Runo M.C. (2013). - The roles of livestock in developing countries. Animal, 7 (s1), 3-18. doi:10.1017/S1751731112001954.

15. Rushton J. (2017). - Improving the use of economics in animal health - Challenges in research, policy and education. Prev. Vet. Med., 137 (Pt B), 130-139. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.11.020.

16. Rushton J., Huntington B., […] & Mesenhowski S. (2021). - Roll-out of the Global Burden of Animal Diseases programme. Lancet, 397 (10279), 1045-1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00189-6.